Harriott Sophie Newcomb, 1855-1870

Harriott Sophie Newcomb, 1855-1870

Sophie, as she was always called, was Josephine and Warren Newcomb’s second child. A boy had been born in 1853 but died at birth. She was close to both parents and also to other family members and her mother’s letters tell of a joyful child with many friends. Her mother was proud of her (so good in French, so admired by all, quick with a hug for an uncle, generous with presents to cousins). She was a classic only child: “really companionable for any one, from age to infancy.” Josephine Newcomb wanted for Sophie, “a brilliant education…. there is no sacrifice I would not make, to have my child a true noble cultivated woman….”

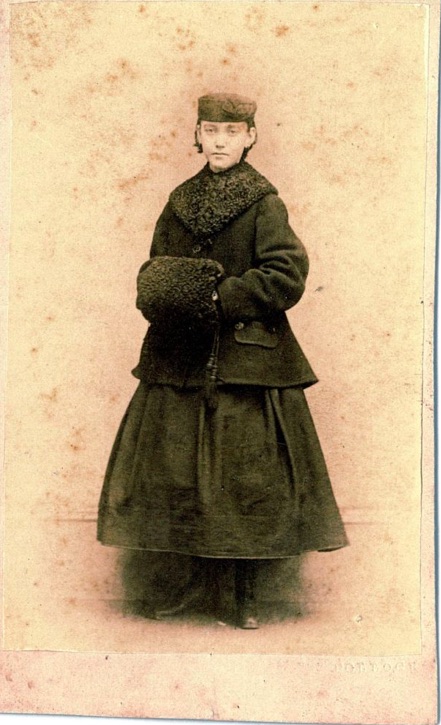

H. Sophie Newcomb, ca. 1864. University Archives, Tulane University.

This print may have been taken in Paris where the Newcombs spent part of the Civil War years. Sophie remained close to aunt Ellen Henderson and her children, as well as some French cousins.

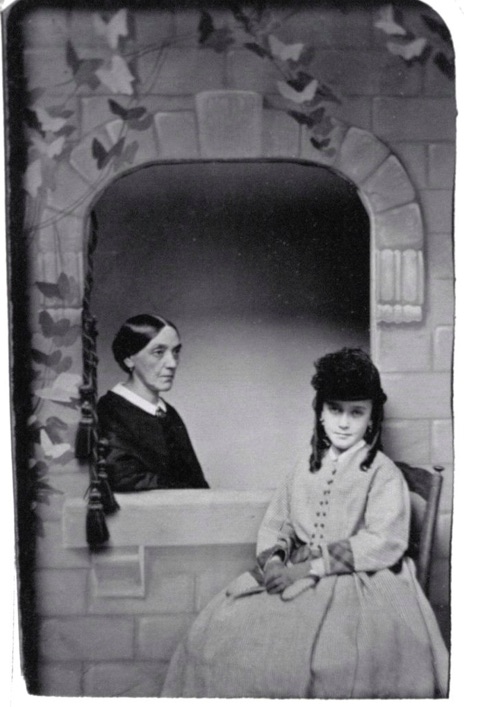

Josephine Louise Newcomb and H. Sophie Newcomb, 1866. University Archives, Tulane University.

It has been assumed that this is a studio print meant to show JLN and Sophie grieving for Warren Newcomb, but the woman here could also have been Ellen Henderson. The families were very close, which makes their schism later in the court case all the more complicated. If this photograph is JLN she does indeed look transformed by sadness.

Sophie’s Death, 1870

In the letters Sophie appears as a normal child in terms of health. Yes, she got sick sometimes but she also recovered quickly. Yes, her mother worried but these worries seem reasonable and normal. However, at the end of 1870, on December 9 in the Fifth Avenue Hotel, the doctor came and diagnosed her with diphtheria. The sickness took a quick toll. She died on December 16. Her last words, documented and annotated in a poem by a friend, were: “Mamma take me on your lap ….. Mamma, how dark it is.”

Curls clipped from Sophie’s head on her death. Newcomb Archives, Tulane University. For more information on items JLN retained and finally found a home for at Newcomb, see here.

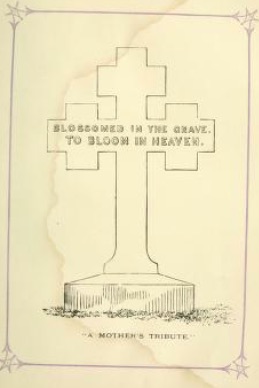

From a memorial booklet in Sophie’s memory. Printed, 1871. Copy available online from the Internet Archive.

More on the Memorial Booklet

By December 1871, perhaps on the date of Sophie’s death one year earlier, the memorial booklet on her life was published and distributed. This was a small forty-eight page book that contains a compilation of her school work and a biographical statement on her life. Within the book is a poem, giving the account of Sophie’s last moments, documented and annotated in a poem by a friend, “Mamma take me on your lap ….. Mamma, how dark it is.”

Memorial booklets were not so common as other forms of mourning, but known to J.L. Newcomb. She had such an 1869 book in her own collection, in memory of a well-known attorney Daniel Lord, though it is unclear if she had it before Sophie’s death since she wrote of it only in 1872.

Sophie’s memorial book is attributed to Josephine Newcomb, at least in the cataloging records of New York Public Library. Either she had the presence of mind to make it, to focus on remembering Sophie in a tangible way, or someone else well known to them both, did. It is a generous work since included are the types of memories usually forgotten: how Sophie once won a prize in French, how she thought autumn the best season, how she smiled and danced.

Inscription showing both the gift of the Memorial Booklet to Mrs. Hawks and then its likely gift to New York Public Library, with inscription crossed out. This particular copy is available online from the Internet Archive.

Mrs. Hawks was the wife of Francis L. Hawks, the Episcopal priest who had married JLN and Warren Newcomb in 1845. The Hawks family, like JLN and Warren themselves, moved between New Orleans and New York. Hawks had been for a short time president of the University of Louisiana, the precursor to Tulane University. JLN maintained contact with the priest’s wife, and thus indirectly with the university in New Orleans, for a long period of time, earlier than her 1886 donation for the women’s college.