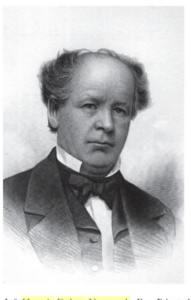

Horatio Dalton Newcomb, 1809-1874

Continued from entry on list of those mentioned in the letters

….

H.D. Newcomb was to become a prominent Louisville, Kentucky businessman and civic leader. Every account of him makes note of his wealth, his “colossal fortune.” He was twenty-one years old when he made his way to Louisville and began working as a clerk in a small business. Within five years, he was a thriving merchant in the wholesale liquor business and began widening his business to include groceries. Warren was invited to join him and together they formed H.D. Newcomb & Brother. In 1840, the brothers went into the exclusive sale of sugars, molasses, and coffee. Their business was aided by the work of their brother Hezekiah, captain of a steamboat on the Tennessee River, who directed a sizable portion of the trade on the Tennessee River to them. This was the first of Horatio’s major business successes.

In 1850, Horatio supplied the capital to save from failure the cotton manufacturing firm of Cannelton Cotton Mills, at Cannelton, Indiana. The mill, which primarily employed women and girls, was said to have production “unprecedented in the history of modern manufactures” and became the source of the bulk of his fortune. With another brother, Dwight, Horatio leased the Cannelton Coal Mines and turned that business over to Dwight after a few years. By 1859, Horatio was one of the wealthiest men in Louisville.

In 1861, he was elected a director of the Louisville & Nashville Railroad and soon devoted his energy, talent, and resources to building and extending the railroad. In 1868, he was elected president, and reelected each year until his death. It is this occupation for which he was widely known and now remembered.

However, it is not so much Horatio’s business acumen and wealth that interests us here, but rather the possible relevance of the scandals and court cases in which he was associated. These illuminate something of JLN’s fear of being wrongly declared insane and institutionalized against her will. The first scandal concerns his first wife; the second, his second wife; and the third, his son Victor. The commitment to an insane asylum of one of Horatio and Warren’s first cousins, H.K. Newcomb, may also have contributed to her preoccupation with insanity.

The first scandal concerned his wife Cornelia Reed, the daughter of a well-known Kentucky family, to whom he had become engaged in 1838. They had four children: Horatio “Victor” (b. 1844, d. 1911); Ernest (b. 1847 or ‘48, d. 1852); Herman (b.1849, d. 1870); and Cornelia (b. abt 1850, d. 1852). At the time of the 1850 U.S. Census, Warren and Josephine were living with Horatio, Cornelia, and their three children. Then in 1852, Cornelia, “while laboring under a temporary derangement of mind, produced by recent sickness, on the night of the 21st [December], took her four children to the attic, and threw them out of the window to the pavement below. Ernest, a boy about five years of age, was killed outright, and the smallest, a little girl, was picked up in a dying condition. The other two children, though greatly injured, are in a fair way to recover.” (The Sun, [Baltimore, Maryland] 12-28-1852)

The daughter, Cornelia, died during the night. Victor and Herman survived. Mr. Newcomb then placed his wife in the “McLean Asylum for the Insane” at Somerville, Massachusetts, known for offering a bucolic setting and humane approach to mental illness, and located in the town where her sister would reside. Horatio and Warren’s sister Mary came to live with the family in Louisville.

There is no mention of this tragedy in JLN’s letters. Yet, she and Warren were living in Louisville at the time, possibly with the family. However, JLN’s fear of being unjustly institutionalized for insanity may well have stemmed from the treatment accorded her sister-in-law. Cornelia was never tried in a court of law; never found to be guilty of murder, or legally “insane.” Yet she was institutionalized for the remainder of her life. Although institutionalizing Cornelia may have been considered more humane than declaring her legally insane or trying her for murder, it is possible that JLN also understood this event as the way powerful men exerted their control over women.

In 1871, Horatio was able to influence the Kentucky Legislature to pass an act by which the grounds for divorce were expanded to include cases where the husband or wife was incurably insane. Under this act, Horatio was divorced from Cornelia in May 1871.

One month after the act was passed, Horatio married Mary Cornelia Smith (b 1848, d. 1905), about 40 years his junior. The marriage was deemed so unsuitable, no Episcopal minister in Kentucky would marry them and a clergyman had to be brought in from Canada. They had two sons, Warren Smith Newcomb (b. 1872) and Horatio Dalton Newcomb (b. 1873). Horatio senior died in 1874, setting off “the famous domestic tragedy suit, commonly known as the Newcomb case…” At the time of his death, Horatio was president of the Louisville, Nashville, and Great Southern Railroad leaving an estate of approximately two million dollars. Victor Newcomb challenged his father’s will with a resulting decision that decreed his mother, still institutionalized, the lawful widow and gave to her one-third of his father’s estate. On Victor’s side, the Kentucky legislature had also repealed the act allowing his father’s marriage. Thus, this marriage to Mary Smith was declared void, though the children were recognized as legitimate, and received $400,000 each, as specified by will, as did their mother. The liquidation of the estate was reported with great interest in the papers, including the entire listing of artworks sold at auction. The Newcomb mansion H.D. Newcomb built in 1859 at 118 West Broadway, Louisville, became home to the Louisville Female Seminary from 1887-1891. It is highly possible that JLN was aware of the Newcomb mansion becoming home to the female seminary. Whether this influenced her ideas about women’s education is unknown. The home is no longer standing.

Five years after Horatio’s death, Mary Smith, then about 30 years of age, married Richard Ten Broeck, a man 38 years her senior. They had one son in 1879, Richard Ten Broeck, Jr. Ten Broeck, described as a once famous Kentucky turfman, had his own checkered marital union that ended in the suspicious death of his wealthy first wife.

In 1889, in San Mateo, CA, Mary Ten Broeck petitioned the court to appoint a guardian to take charge of Richard Ten Broeck and his property, claiming him to be incompetent. He testified that his wife was trying to poison him and had employed agents to kidnap him so she could control his property. Physicians appointed by the court determined he was not in a condition of insanity to warrant his commitment to an asylum. Mary Ten Broeck’s petition was denied. Richard died in 1897, and Mary moved back to New York.

It is not known if JLN was aware of Mary Ten Broeck’s efforts to commit her second husband. Though Mary Ten Broeck had remarried after being widowed by Horatio, she and JLN stayed in touch. In a letter to Alice Bowman dated November 4, 1898, JLN writes: “I do hope Bessie Smith’s first impressions on you, will continue in depth; her cousin Dalton is very fond of her & said, “Aunt Jo she is like you not in looks but in ways.” Bessie Smith was the niece of Mary Smith Ten Broeck, and at the time, an entering student at Newcomb College. According to Mrs. Chamberlain’s testimony in the court case, Mrs. Ten Broeck called on JLN several times during her last illness and had visited her the last week of her life. Mrs. Chamberlain also reported that during one of those visits, Dalton Newcomb had called on JLN with his mother. As an aside, Mrs. Chamberlain’s daughter entered Newcomb the same year as Bessie Smith.

A third case of insanity involves Victor Newcomb, the only surviving son of Cornelia and Horatio Dalton Newcomb, who was declared insane on the application of his wife Florence W. Danforth, and son, Hermann (b. 1872) in 1899. The family physician testified that Victor Newcomb “was addicted to the excessive use of drugs” (chloral, a sedative and hypnotic). Victor had succeeded his father as president of the Louisville and Nashville Railroad and after a short period of retirement, he moved to New York and organized the United States National Bank. He was said to have been the youngest bank president ever elected in the city of New York. Victor was sent to a sanitorium and after treatment, was declared cured. He filed for a divorce from his wife in 1902, charging her with abandonment and cruelty. At one time estimated to be worth ten million dollars, The Daily News (New Orleans) reported he died a poor man with an estate of less than $30,000. In his will, he left to his former wife and their son “in trust and otherwise large estate, together with a large life insurance on my life” [$200,000]. He also left $4,000 and an annual income of $1400 dollars to a woman he employed as a registered nurse “since my severe accident and illness in 1907.” It is not known what the accident was to which he refers.

In addition to these three cases, there is yet another instance known to JLN of a Newcomb family member being institutionalized for insanity. In a letter addressed to her brother-in-law William Henderson in 1868, she writes “I suppose you have heard of the terrible death, of H. K. Newcomb at Worcester, a friend writing from there tells me he died from exhaustion, trying to get out of the ‘Straight Jacket’ & was the craziest person, that had ever been brought to the Institution…” H.K., Henry Knox, was Warren and Horatio’s first cousin, their fathers being brothers. Death Records confirm Henry Knox Newcomb died in 1868 at age 71 of “Mania -Exhaustion” in a “hospital” in Worcester. Henry Knox Newcomb had been in his earlier life a well-respected member of the community as an officer in the Boston Customs House, crier of courts in Worcester County, and secretary of the Worcester Mutual Insurance Co. One can’t help but wonder if his exhaustive efforts signaled his wrongful institutionalization.

To recap, among the immediate family of H.D. Newcomb were his first wife, Cornelia Reed; their son Horatio “Victor”; and H.D.’s second wife Mary Smith [later, in her second marriage, Ten Broeck] and their sons: Warren and Horatio “Dalton” Newcomb. A first cousin was Henry Knox Newcomb.